Our History

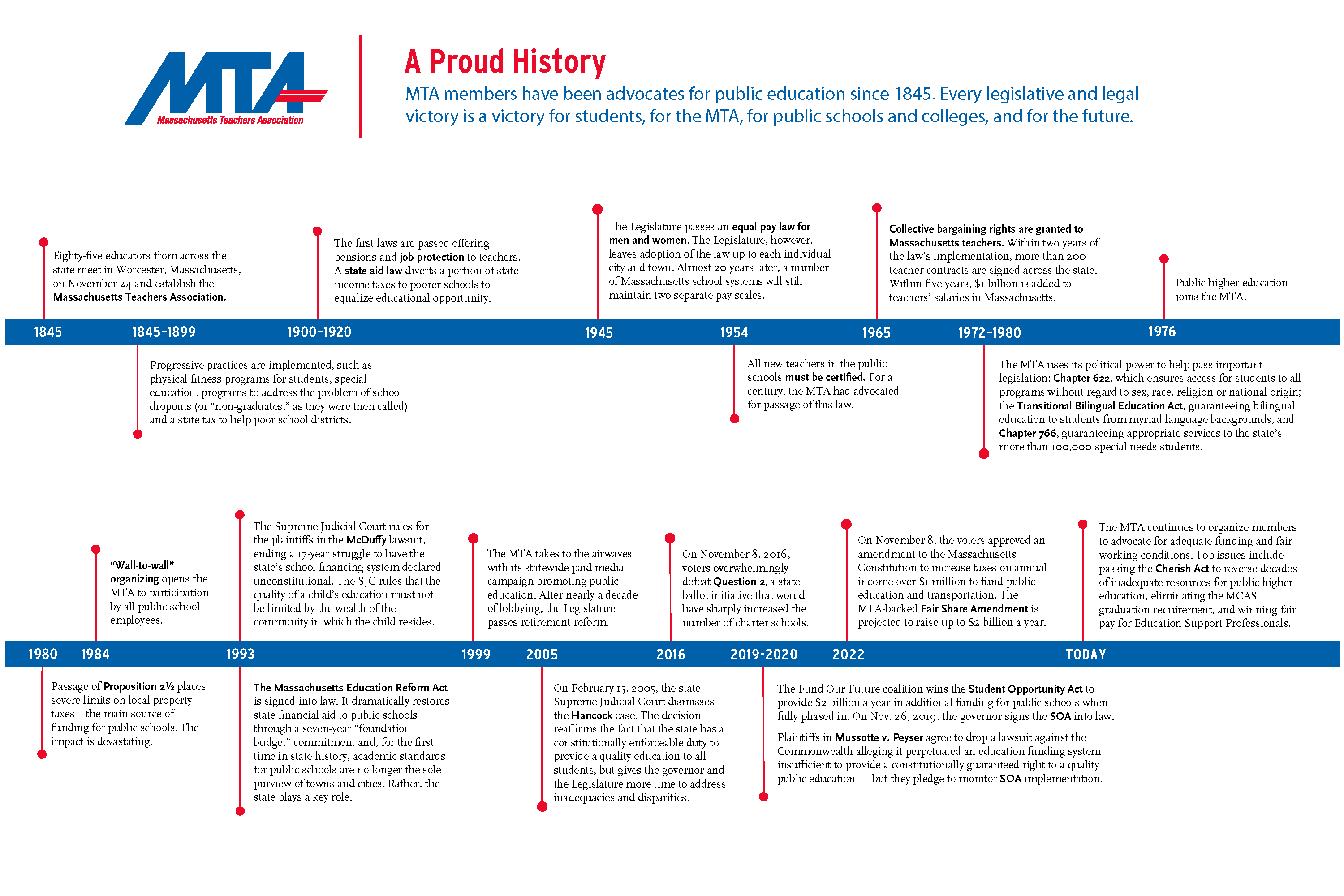

Founded in 1845, the MTA has a rich history of standing up for educators, students and the common good. The association has evolved from an all-male, all-white professional association of teachers and administrators to a multicultural union of preK-12 teachers and Education Support Professionals and public higher education faculty and staff.

Despite the dramatic changes over time, two core missions have remained constant for nearly 200 years: Making sure educators have a voice in teaching and learning, and advocating for fair pay and good working conditions.

In 2023, the MTA launched the MTA History Project, a Public Relations & Organizing initiative to identify, preserve and share stories and artifacts from MTA’s history for the benefit of MTA members, researchers and the general public.

- In 1845, 85 educators establish the MTA

-

The year was 1845. James Polk was sworn in as the 11th president of the United States. Texas became the country’s 28th state. A potato blight led to the Great Famine in Ireland, setting off a wave of Irish immigration to the U.S. And on November 24, 85 educators — all men — met in Worcester at Brinley Hall to establish the Massachusetts Teachers Association. That meeting was at the behest of the Essex County Teachers Association, which had been founded in 1830 and was one of the first county associations in the country.

Times have certainly changed since the organization’s founding, but the MTA is still going strong. Throughout its history, members of the association have supported their students through major upheavals, including the Civil War, World War I and World War II, the Great Depression and the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918, which claimed the lives of about five out of every 1,000 U.S. residents. They are continuing to do so in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In 1845, “practical” male teachers were allowed to join the MTA for a fee of $1 a year while female teachers were allowed only to become honorary members.

The mid-19th century was a period of great change for public education in Massachusetts. There were a number of publicly funded schools in Massachusetts from colonial times, including in Dedham, where the first taxpayer-funded school in the country was authorized in 1644. (Boston Latin, the oldest continuously operating public school in the nation, was run out of private residences until it moved into a schoolhouse in 1645.)

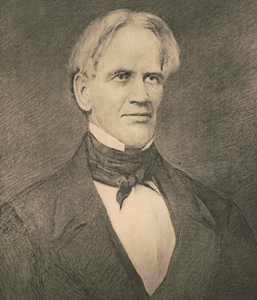

It wasn’t until the mid-19th century that Massachusetts had a statewide system of free, universal public education. The champion of that system was Horace Mann, a lawyer and Massachusetts state senator who in 1837 became the first secretary of the newly established Board of Education. Mann propounded six main principles of education for what were then called “Common Schools” that still resonate today:

- Citizens cannot maintain both ignorance and freedom;

- This education should be paid for, controlled and maintained by the public;

- This education should be provided in schools that embrace children from varying backgrounds;

- This education must be nonsectarian;

- This education must be taught using tenets of a free society; and

- This education must be provided by well-trained, professional teachers.

The Common School movement spread across the country. Then, as now, Massachusetts was in the vanguard of public education, having passed the nation’s first compulsory education law in 1852.

In an address to the MTA’s Annual Meeting of Delegates, held at Faneuil Hall in Boston and recounted in the periodical The Massachusetts Teacher in 1854, William Harvey Wells, an early MTA leader, said: “If there is a portion of the world in which the blessings of a free and universal education are more fully enjoyed than in any other, I trust we may say, without boasting, that place is Massachusetts.”

As more schools were developed, more female teachers were hired, beginning in the 1850s. According to a history of public education produced by PBS, despite low salaries and poor working conditions, “Still, women flocked to teaching. Not only were they grateful for the salary, however meager; they also welcomed the independence and sense of purpose teaching gave them. … Teaching gave women a window onto a wider world of ideas, politics and public usefulness.”

“There are many respectable schools in Massachusetts in which the number of pupils is as great as 60 or 70, and even 80 or 90, for each teacher.”

William Harvey Wells, 19th century editor of The Massachusetts TeacherIn his address, Mr. Wells described some of the working conditions that prevailed at the time: “The labors of many teachers, if faithful in the discharge of their duties, are so constant and arduous during the day, that they have no strength left, at the close of school hours, either for personal improvement, or for a review of lessons to be heard on the following day.” The problem? “There are many respectable schools in Massachusetts in which the number of pupils is as great as 60 or 70, and even 80 or 90, for each teacher.”

Given that large number, it is not surprising that another article in The Massachusetts Teacher that year focused on “The Evils and Remedies of Whispering, or Communicating in School.” In this “prize essay,” Mr. Daniel Mansfield of Cambridge complains of students “whispering” about such matters as “the next sleigh ride, the new bonnet of one, and the shabby dress of another.” If all 60 students in a class whispered twice an hour during a three-hour, half-day session, then there would be “360 whispers in one session” — an intolerable distraction.

In addition to focusing on how to improve the lot of teachers, the early MTA publications focused on fundamental issues of pedagogy. One example is a Massachusetts Teacher article from February 1854 titled “Teaching to Think.” It begins, “However immature his mental capacities or unripe the more primary processes of development, the pupil must be taught to think. … The widest compass of the instructor’s field of toil is to furnish food for the mind, present inducements to energy, supply the higher impulses to an elevated course of acquisition, and to precede the pupil with the aids of demonstration and explanation. Impart mind, or give thought — he can do neither.”

These were among the areas covered in new institutions known as “Normal Schools,” which were experimental teacher training schools established during Mann’s tenure at the Board of Education. If public schools were going to be required in communities throughout the state, more teachers would have to be trained. The first state-supported Normal School in the country was founded in 1839 on the northeast corner of the historic Lexington Battle Green. It later moved and evolved into Framingham State University.

In the 19th century, the MTA fought for such progressive education ideas as physical fitness programs for students, special education for the handicapped, programs to address school dropouts, and a state tax to help poor school districts. Parallels can be found today, as the MTA is currently fighting for a bill to guarantee 20 minutes of recess for elementary school students, wraparound services to meet the needs of at-risk students and — with passage of the Student Opportunity Act — more state funding to help low-income students and students with special needs.

The MTA also began to stand up for female teachers many years ago. In 1860, The Massachusetts Teacher includes a quote decrying “school systems in which female teachers are seldom employed and ignorant men are preferred to competent females.” Four years later, an article speaks up for better pay for female teachers. “In light of justice and of humanity, we submit that it is not creditable to the intelligence and the educational status of the Old Bay State, that the female teachers who are spending the very best portion of their lives, wearing out soul and body in the exhausting labors of the school-room, should not receive a fair compensation for their labors.” That pay in certain towns is described as $1.50 for a week’s work, plus $2.50 for board.

One-room school houses, like this one in Lancaster, Mass., were a common place to be educated in the 19th century. (Image courtesy of Lancaster Historical Society) The MTA weighed in on issues of social and political significance in its early days, as it does today. When the Civil War was declared in 1861, the association was enthusiastic in its support of the Union, noting proudly the increasing numbers of members who left their classrooms to join the cause.

After peace was restored, an 1866 issue of The Massachusetts Teacher defended “equal rights to all men, irrespective of race or color.”

Also important to the organization from the start was the status of the teaching profession. A complaint found in The Massachusetts Teacher may sound familiar: “Our ears are often assaulted with woeful lamentation over the low estimation in which the profession of teaching is held.”

That said, the MTA itself was apparently held in high esteem. School districts released teachers to attend the MTA’s annual meetings. In 1865, the editor of The Massachusetts Teacher breathlessly published an article with the headline “Twenty-five Hundred Massachusetts Teachers in Convention Assembled! The Largest Gathering of Educators Ever Seen in America! The Old Bay State Thoroughly Waked Up!”

The writer concluded, “So inspired was the occasion, that even the silver-haired school masters felt themselves young again; and the humblest teachers held up their heads and modestly exclaimed, ‘Really, we think, after all, that we are somebody.’”

This is the first in a series of articles marking the 175th anniversary of the Massachusetts Teachers Association. This is a lightly edited version of the article written by Laura Barrett that appeared in the Spring 2020 issue of MTA Today. This article incorporates research done for The Faces and Voices of the Massachusetts Teachers Association: Celebrating 150 Years of History.

- In the 1900s, MTA wins rights and benefits for members

-

By the turn of the century, MTA was a firmly entrenched member of the education establishment. Its conferences were attended by such notables as educator and author Booker T. Washington and Harvard University President Charles W. Eliot. But membership in the establishment came at a price.

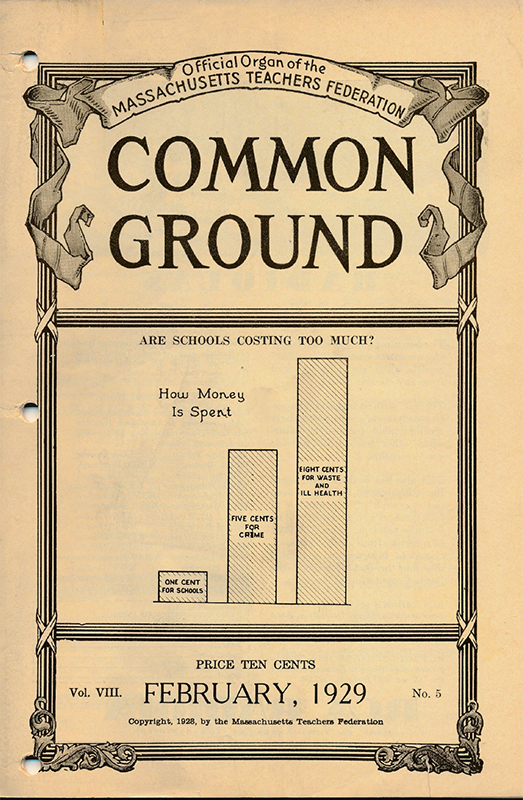

Many felt MTA had ceased to focus on the problems and concerns of rank-and-file educators. Thus, on Feb. 8, 1911, Ernst Makechnie of Somerville gathered with fellow educators from Attleboro, Leominster, Lowell, Lynn, Malden, New Bedford and Newburyport, and founded the Massachusetts Teachers Federation. Three years later, the MTF launched a new publication called Common Ground. In 1919, the MTF merged with the MTA. The merged organization continued to be called the MTF until it changed its name back to the MTA in 1953. In these articles, we refer to the merged organization as the MTA for clarity.

Revitalized under the new structure, the MTA now organized its members by local associations and encouraged its members to be active in both the educational and political arenas.

Many issues addressed in the early 20th century have parallels today, including coping with a pandemic.

The influenza pandemic of 1918 and 1919 — known as the Spanish flu — hit Massachusetts hard. Fort Devens, in the towns of Ayer, Shirley and Harvard, was a major source of the outbreak in the U.S., with one 1918 report noting, “On Sept. 1, its barracks were jammed with 45,000 soldiers waiting to be shipped to France. By the end of that month, Fort Devens was a charnel house filled with the dead and dying.” By the time the pandemic was over, the virus had killed at least 50 million people worldwide — 675,000 of them Americans.

Most urban schools across the country closed after the second wave hit in 1919, according to the journal Health Affairs, including those in Boston, Fall River, Lowell and Brookline.

Despite the magnitude of the problem, there appears to have been only passing reference to the earlier pandemic in the MTA’s publications from those years. Issues of merit pay, whether “child-centered” education was the right approach, and the routine activities of local associations — many of which were called “clubs” — are described at length. The war in Europe, which was still going on when the first wave hit, was discussed in several essays. But the lack of any mention of the pandemic or school closures in the MTA’s publications is in sharp contrast to today’s intense focus on COVID-19. Media coverage of the pandemic was also minimal by today’s standards.

What Common Ground did focus on during those years was improving teaching conditions. In the April 1918 publication, that platform included support for:

- Equitable salaries for teachers.

- The enactment of a retirement law.

- The enactment of a tenure law.

- More democratic control of schools in ... making rules for the conduct of the schools, choosing the textbooks, arranging the courses of study.

- Vocational education.

- The last item in the 12-point platform was support for the 18th Amendment to the Constitution, prohibiting the manufacture, transportation or sale of alcohol. Prohibition was ratified in January 1919.

By the 1920s, the MTA had scored some impressive victories:

- A retirement law that offered educators pensions for the first time;

- A tenure law that offered some minimal job security;

- A minimum salary law that put a floor under teacher earnings; and

- A state aid law that diverted a portion of state income taxes to poorer schools to equalize educational opportunity.

On that score, the principles described in Common Ground are nearly identical to the requirements for public school funding laid out in the 1993 McDuffy case and codified in the Massachusetts Education Reform Act of that year. Paul R. Mort, the 1931 author of “The Financing of American-Level Schools,” wrote:

The influenza pandemic of 1918 and 1919 — known as the Spanish flu — hit Massachusetts hard. Boston Red Cross volunteers assembled gauze masks for use at Fort Devens, which was a major source of the outbreak. Most urban schools across the country closed after the second wave hit in 1919. (Photo courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) “The principle of equalization of educational opportunity demands that the state shall define a satisfactory program of education below which no community in the state shall be permitted to go.” In today’s terms, that’s the foundation budget.

“It then follows that the state must provide a system of financing this program of education, either from state sources or from a combination of state and local sources so devised that the burden of the minimum program shall fall upon the people in all localities according to their taxpaying ability. In this principle will be noted both the promise of adequate educational opportunities for boys and girls and the trend toward equity in taxation.”

Women continued to be second-class citizens in education, as in society as a whole. They were routinely paid less than men. For example, in 1918 — two years before women won the right to vote — the maximum annual salary for a female high school teacher in Saugus was $750, while for a man it was $900. Top salaries for elementary school teachers, disproportionately female, were even lower: $650. In addition, the state Supreme Judicial Court codified discrimination against married female teachers.

An MTA survey of 1926 found that almost 30 percent of cities and towns did not permit married women to teach. In Chicopee, the School Committee summarily fired all married women teachers, except those protected by tenure. And when the Hopedale School Committee’s dismissal of a married female teacher was challenged, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court came down against the teacher. Its ruling stated: “The School Committee acted in good faith, without animosity, and for what it considered to be in the best interests of the schools.”

An MTA survey of 1926 found that almost 30 percent of cities and towns did not permit married women to teach.

Financial concerns were paramount after the stock market crashed on Oct. 29, 1929. In the ensuing years, teacher pay was reduced by anywhere from 5 percent to 20 percent, and many educators lost their jobs. Hugh Nixon, the MTA’s first full-time executive secretary, wrote: “We must not allow the present economic depression to lead to an educational depression. Let us help mitigate the sufferings of those less fortunate than ourselves, especially the children for whom we are responsible because we are teachers.”

Then as now, the MTA was willing to take on monied interests to make sure public schools were properly funded. When critics complained that the MTA was applying too much pressure in support of members’ interests, the association responded: “We should not be frightened off by the tactics of vested interests who fulminate about the ‘selfish lobbies’ of teachers. When tax-dodgers begin to call us names, it is a sign that our programs are getting results.”

This is the second in a five-part series on the history of the MTA published in 2020, the 175th anniversary of the MTA’s founding. This is a lightly edited version of an article written by Laura Barrett that appeared in the Summer 2020 edition of the MTA Today. This article incorporates research done for The Faces and Voices of the Massachusetts Teachers Association: Celebrating 150 Years of History.

- Women educators gain leverage during WWII

-

The Great Depression created hardships for many in public education, as teacher salaries were cut and schools were closed. Women paid the highest price. They were paid less than men in the first place and they were often fired once they married. That practice was upheld by the courts in 1938 in a case involving a Somerville teacher.

When young men left the classroom in large numbers to fight in World War II, women teachers found they had some leverage. The MTA commented, “Some communities will soon be calling back the married women who were so unceremoniously dropped when other people wanted their positions.”

The war was a frequent topic in MTA publications. Students were encouraged to bring in nickels, dimes and quarters to buy savings stamps to help finance the war effort. Patriotism was expected. In a 1943 article, teachers were exhorted to pledge: “We will foster the physical and mental health of children and youth, and see that remediable defects are promptly corrected, remembering that the duties and strains of war require strong bodies and healthy minds.”

As the war drew to a close, women’s rights took a step forward.

In 1945, after years of lobbying by the MTA, Massachusetts passed the Equal Pay Law for men and women who do comparable work. However, the Legislature left adoption of the law up to each individual city and town. Almost 20 years later, a number of Massachusetts school systems still maintained two separate pay scales.

Today, of course, that would be illegal. But the changes don’t mean women are treated equitably in hiring and promotion practices. Although there are now about three times as many female teachers as male teachers in Massachusetts, male superintendents outnumber females 201 to 132, according to a 2021 Rennie Center report.

The postwar years saw an unprecedented boom in salaries — except among educators. In a 1946 Massachusetts Teacher article titled “Shall I Return to Teaching?” a sailor who had taught in Brockton asked, “Wouldn’t I be better off staying in the Navy? The pay is much better in the Navy, and now that the actual struggle between life and death has been removed, it is a much more leisurely life.”

The sailor continued, “I actually dreaded meeting my first class after three years in the naval service.”

His attitude changed when his 35 students arrived. “I felt there still were children in the world who could laugh, talk, and giggle,” he wrote. “I felt at home with them, as if I hadn’t left them at all.” He concluded that teaching was his life’s work after all.

The salary was a continual problem, however, and some rural districts paid so poorly that they had a hard time retaining staff. In 1950, average annual salaries listed for selected trades showed classroom teachers at the bottom:

- $4,675: Steam-railroad crews

- $4,233: Heavy construction

- $4,142: Newspaper

- $4,034: Plumbing

- $3,457: Carpenters

- $3,350: Classroom teachers

The MTA frequently called for more state funding to increase spending and better equalize resources across districts. In a 1945 article titled “Cherishing the Public Schools,” the MTA’s director of research cited the same constitutional provision relied on in later lawsuits to make the case for more funding. “The differences in financial ability among the cities and towns in Massachusetts are very great,” the author wrote. “Newton is three times as able as Fall River or Taunton to support an educational program.”

It was the same argument that would be made decades later — in the 1993 McDuffy case, which led to increased state aid to low-income districts, and again in the legislative battle in 2021 for the Student Opportunity Act.

Pay was one issue. Respect, autonomy and the rights of educators were others. Teachers were among the professionals targeted by McCarthyism, which flourished from 1950 to 1954.

By 1950, anyone entering public service in Massachusetts had to take an oath vowing that he or she was not a communist. The Cold War had begun. MTA fought to eliminate loyalty oaths and other forms of McCarthyism:

“The schools are already doing more than all other agencies combined to teach love of country through the study and appreciation of our national government, history, music and literature. Also, the daily salute to the flag and Pledge of Allegiance ought to satisfy any doubters.”

In the 1950s and 1960s schools held “duck and cover” drills because of the threat of a nuclear attack. (Creative Commons photo) The Cold War left its mark in another way. Where we now have active-shooter drills in our schools, in the 1950s and 1960s students were taught to “duck and cover” in case of a nuclear attack.

But not all of the association’s efforts were on such a large scale. In 1951, the MTA won passage of Chapter 219, a law “prohibiting the manufacture and sale of bean blowers.” It also banned slingshots, bludgeons and “metallic knuckles.”

The rights of women teachers and the efforts to raise professional standards gained ground in the postwar period.

In 1953, Governor Christian A. Herter signed a law forbidding the dismissal of married women teachers. One year later, Massachusetts became the last state in the country to require all new teachers in the public schools be certified. The MTA had supported this law for more than a century.

The Civil Rights movement had a lasting impact on schools and on the MTA.

In 1954, one of the most important decisions ever handed down by the U.S. Supreme Court — in Brown v. Board of Education — struck down the “separate but equal” doctrine and ordered desegregation of the public schools.

The decades since have seen uneven progress, though. Desegregation efforts were resisted in the North as well as the South, and Boston was a center of the fight against “forced busing.” Recent Black Lives Matter protests show how much still needs to be done. As reported in The New York Times last year, “Racial segregation in public education has been illegal for 65 years in the United States. Yet American public schools remain largely separate and unequal — with profound consequences for students, especially students of color.”

The 1950s also saw a shift in focus, from schools fostering “strong bodies and healthy minds” to aid in the military effort to a major focus on science and technology.

By the end of the decade, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, and Washington responded with the National Defense Education Act, pumping $1 billion into the schools and beginning a period of unprecedented growth.

There was plenty of room for improvement. According to statistics for 1960:

“Of every 10 students in fifth grade, only six will finish high school. Of every three students who enter high school, only two will finish. Only one elementary school in five has a library. And chances are nine in 10 that an elementary student will be taught by a non-college graduate.”

In November 1965, Governor John Volpe signed collective bargaining rights for teachers into Massachusetts law. Standing beside him is MTA Executive Secretary William H. Hebert. Education became a focus of President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society programs in 1964-1965, with new laws designed to attack poverty and racial injustice. The Elementary and Secondary Education Act, signed into law on April 11, 1965, provided new federal funding for public education, mainly through the Title I program targeted to assisting low-income students.

That year brought another big change. Until 1965, the only way MTA members could win better wages and working conditions was to make their case to local school committees. The committees were under no obligation to negotiate with them.

A new generation was no longer willing to go begging. While private-sector employees had won collective bargaining rights in the 1920s and 1930s, the public sector had been left behind. Finally, the fight for collective bargaining rights by the MTA and the state affiliate of the American Federation of Teachers succeeded.

On Nov. 17, 1965, with newly installed MTA Executive Secretary William H. Hebert at his side, Governor John Volpe signed Chapter 763, granting collective bargaining rights to Massachusetts teachers.

In a column for The Boston Herald, Hebert commented: “For many years, teachers have argued with justification that they are unappreciated as professional people. Their salaries in respect to their education and responsibilities are evidence of this injustice. Now they have a chance to right this wrong.”

Within two years of its implementation, more than 200 teachers’ contracts were signed across Massachusetts. Within five years of its implementation, $1 billion was added to teachers’ salaries in the state.

The MTA was now both a professional association and a labor union, a dual role that continues until this day.

This is the third article in a five-part series published in 2020, the 175th anniversary of the MTA’s founding. This is a lightly edited version of the article written by Laura Barrett that appeared in the Fall 2020 edition of the MTA Today. This article incorporates research done for The Faces and Voices of the Massachusetts Teachers Association: Celebrating 150 Years of History.

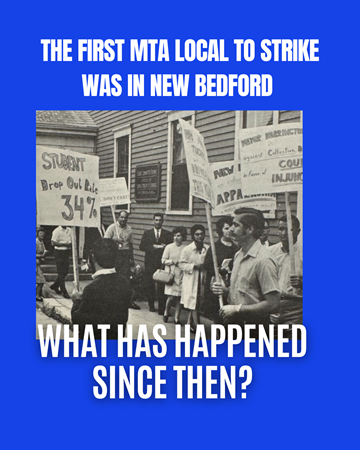

- Strikes, activism mark the '70s and '80s

-

Striking teachers marched in a picket line outside Woburn High School in 1970. Dozens of such actions took place in the 1970s and 1980s as teachers fought for social and economic justice. (Woburn strike photo/Brearley Collection, Boston Public Library) The late 1960s through the 1970s was a period of powerful social change, including the rise of public-sector labor activism, the growth of the Civil Rights Movement, and the drive for women’s liberation.

In 1966, the American Teachers Association, a national African-American teachers’ group with 60,000 members, voted overwhelmingly to merge with the NEA. The ratification vote, which took place at the NEA Representative Assembly, was described by a witness:

“Every state association demanded the privilege of seconding the motion for merger. The Unification Certificate was signed by the presidents and executive secretaries of both organizations while delegates sang ‘Glory, Glory, Hallelujah.’”

In 1968, the MTA opened its Boston headquarters, and a few years later it added regional offices and hired more staff. A strike for economic justice by the New Bedford Educators Association in 1969 was quickly followed by teacher strikes in Woburn, Brockton, Somerville, Burlington, Fall River, Grafton and Franklin.

During the two-week Franklin strike, in 1977, Superior Court Judge John M. Greaney jailed more than 80 teachers and fined the association $350,000.

One Franklin teacher who went to jail described her ordeal to the MTA: “We explained to the kids that their mother was going to jail. But try telling that to an eight-year-old. The first thing he wanted to know was, ‘How long? For a year?’

“I couldn’t even answer him. And then there are the fines and lost salary ... I don’t know what it will mean. But we’ll manage. I did something I believe in very strongly, and I’d do it again — no matter what it cost.”

Another jailed teacher shared his memories: “I was settling down to sleep when another inmate yelled up from a lower tier: ‘Hey, Teach, is this what you call collective bargaining?’”

"Hey, Teach, is this what you call collective bargaining?"

Question by an inmate to a teacher jailed during the 1977 Franklin strikeEd Sullivan, a former MTA Executive Director-Treasurer who was a staff attorney during that period, recalled those heady days.

“You could feel the electricity,” he told MTA Today. “A new type of activist leader was emerging. It was still a professional association, but we were on the move.”

Speaking of the Franklin strike, he said, “Teachers from other locals came out in droves to support them.”

The MTA, whose members were then and still are predominantly women, also fought against continued discriminatory practices.

In 1973, the MTA established the Committee on the Advancement of Women in Education. Six years later it celebrated a major victory when the state Supreme Judicial Court ruled that it was unlawful sex discrimination to exclude pregnancy from sick-leave coverage.

The fight for ethnic minority rights also gained new momentum in the 1970s, first at the NEA and then in state affiliates.

In 1979, the MTA established its Minority Affairs Committee. Today, the MTA Ethnically Marginalized Affairs Committee is one of several association groups fighting for racial justice.

Louise Gaskins, a leading spokesperson for minority affairs at the MTA and the NEA, said that Black educators had struggled for equal treatment for years. She concluded, “Until you let people in power know that you are interested in changing how things are, things will remain the same. Our goal is simple: We intend to catch up.”

In 1974, the state’s collective bargaining law for municipal, county and state public employees was strengthened significantly, with new provisions under Chapter 150E. This law allowed state employees to bargain over wages for the first time.

One campus activist told the MTA: “What existed [before] was basically a weak system of reaction — some faculty member would get fired, and the others would get together and hire a lawyer to defend him. Or a committee would be elected to handle the problem. But this is changing today. Faculties are winning genuine authority in matters which affect them. The agent for this change is collective bargaining.”

Two years later, in 1976, the MTA voted to allow public higher education employees to join the union.

During this period, the MTA also helped pass important legislation to improve public education for students, including:- Chapter 622, which assured students access to all programs without regard to sex, race, religion or national origin.

- The Transitional Bilingual Education Act, guaranteeing bilingual education to students from myriad language backgrounds.

- Chapter 766, guaranteeing appropriate services to the state’s more than 100,000 special needs students.

Ginny McCabe, standing at a polling place in Cambridge on Election Day in 1980, was one of many MTA members who urged voters to reject Proposition 2½. Its passage was devastating. The promise of the 1970s gave way to despair in 1980 with passage of Proposition 2½, a statewide ballot question that strictly limited local property tax collections and eliminated fiscal autonomy for school committees. The MTA had fought the ballot measure and even put a competing, more moderate question on the ballot — but those efforts did not prevail.

The impact was devastating. It was many years before increases in state aid began to replace lost local property tax funds. In 1981, the MTA reported that the City of Cambridge proposed cutting 439 school employees while the Quincy School Committee voted to close five schools and lay off 226 teachers, among many other deep cuts.

One 25-year veteran from the Berkshires wrote: “Like an invisible thief, Proposition 2½ has stolen one of my irreplaceable possessions: my career. It might have stolen my car; I could have replaced it. It might have taken my wallet; I could have found compensation. But it has taken that which I have nurtured and loved for a quarter century. I have not burned out. My zest for teaching holds energy enough for countless more years. I was put out.” New teachers were laid off in droves and positions were left unfilled. Years later the impact could still be felt, as many schools had large cohorts of older and younger teachers, but few in the middle.

The challenges to public education were not only financial. In 1983, “A Nation at Risk” was published. The report contributed to growing claims that public schools were failing.

A year later, almost 700 MTA members gathered at a special delegate assembly at Burlington High School to hammer out reform proposals based on their own experiences. Member voices informed the MTA’s advocacy in the debate over Chapter 188, the education reform law signed by Governor Michael Dukakis in 1985. The MTA praised the new law for funding equal opportunity grants and early childhood learning incentives but faulted it for not doing enough to limit class sizes or raise teacher salaries.

Also in the 1980s, wall-to-wall organizing opened the union to participation by every member of the family of Massachusetts public education, including school secretaries, custodians, bus drivers, teacher aides, food service personnel, library aides, laboratory technicians, telephone operators, medical records personnel, accountants, book-keepers, mail room clerks, computer programmers, library and reference assistants, audio-visual technicians, and others.

What didn’t change was the MTA’s struggle for members’ rights, benefits and professional dignity, leading to strikes in nearly two dozen locals in the 1980s.

When asked about teacher strikes by reporters, MTA President Nancy Finkelstein explained: “Teachers are frustrated because in the midst of the Massachusetts Miracle, they have been left behind. If it is true that a rising tide lifts all ships, too many teachers are still waiting at the dock.”

This is the fourth article in a five-part series that began in 2020, the 175th anniversary of the MTA’s founding. This is a lightly edited version of an article written by Laura Barrett that appeared in the Winter 2021 edition of the MTA Today. This article incorporates research done for The Faces and Voices of the Massachusetts Teachers Association: Celebrating 150 Years of History.

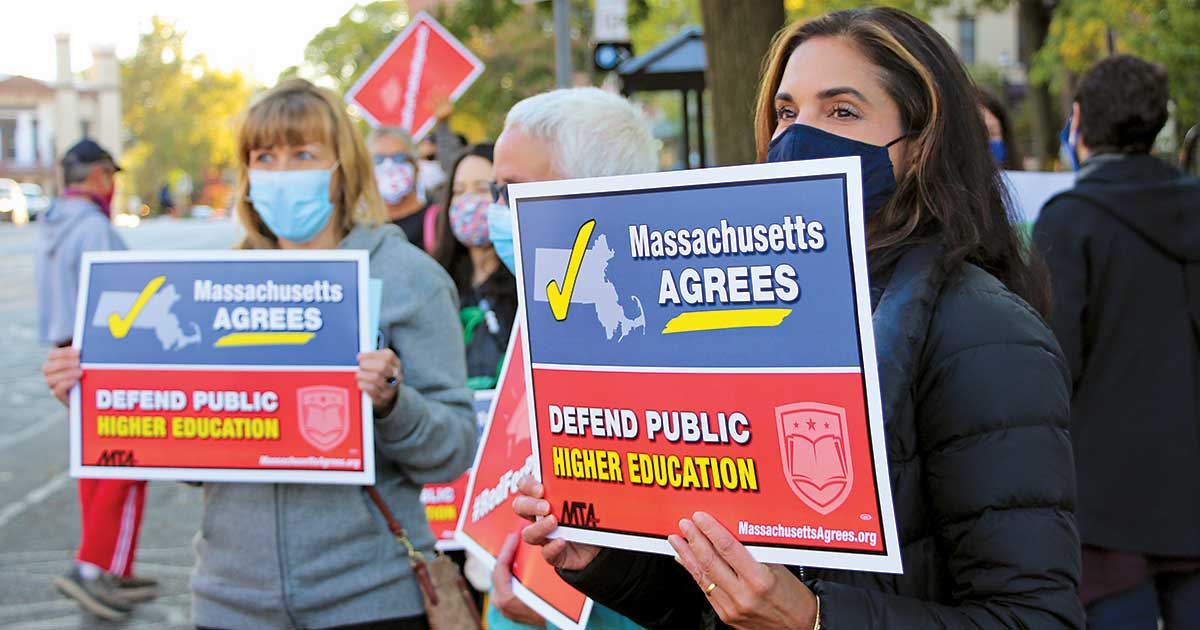

- Members lead funding fights in '90s and beyond

-

Deep staffing cuts in the early 1990s left computer labs unused and classes with more than 35 students in Rockland’s elementary schools. The Education Reform Act of 1993 helped alleviate funding shortfalls. A decade after the anti-government organization Citizens for Limited Taxation won Proposition 2½ in a 1980 ballot vote, the group was back again with an equally threatening initiative to slash state taxes and budgets by billions of dollars. The risk to public schools and public higher education posed by Question 3 was enormous.

The early polls were not promising. This time, the MTA organized as never before, engaging in a massive “No on 3” campaign throughout 1990 with other unions and parent and community groups.

MTA members were the backbone of the local actions, passing out leaflets, holding signs and organizing public forums. As was the case in a much later fight against a ballot initiative to expand the number of charter schools, many analysts felt that educators — among the most trusted professionals in our society — had a huge impact on the outcome simply by telling their friends, relatives and neighbors about the harm the measure would cause. In the end, Question 3 was resoundingly defeated, 60 percent to 40 percent.

“We did it!” wrote then-MTA President Rosanne Bacon. “It is a triumph of reason over anger. The message for us is clear. When we work together we can win!”

The celebration was short-lived, however. A recession had taken hold, and when Republican Governor William Weld took office in January 1991, he was intent on cutting spending rather than raising taxes to address the threat. The cuts came quickly.

The hit to public higher education was immediate and reverberated nationwide. In March 1991, the chair of the NEA’s National Council on Higher Education was quoted as saying, “It is a travesty and a disgrace for this indignity to be heaped upon such great public colleges and universities. It will set the worst possible precedent because Massachusetts is viewed as a national leader in higher education.”

Furloughs were imposed on faculty and staff, and programs vital to students were slashed.

“Outraged faculty, librarians, staff, and students at the University of Massachusetts’ Amherst and Boston campuses conducted ‘No Business as Usual’ for two days in mid-April to protest the continuing savage budget cuts against the university and public higher education,” an MTA Today article stated.

Public schools were also hit hard when the state slashed local aid, while municipalities were prevented from making up for the loss without a Proposition 2½ override. Low-income communities were impacted the most. In 1991, MTA Today reported that Holyoke’s elementary schools no longer offered music, art, physical education, foreign languages, guidance services, home economics or industrial arts.

According to that account, “Classes in Holyoke are jammed with up to 42 students,” the result of the layoff of one third of the teaching staff of 750. “Next to the crammed classrooms are empty ones. Teachers in two of the three middle schools have no preparation time."

Critics of public schools, burned by their loss on Question 3, were quick to blame educators. They clamored for “reform” and demanded salary givebacks to make up for the lost funding.

The MTA and the state affiliate of the American Federation of Teachers fought back, proposing funding increases and truly progressive plans for change. The MTA and others also aggressively pursued a lawsuit, first filed in 1978, to establish the state’s constitutional obligation to provide adequate funding to public schools in rich and poor communities alike.

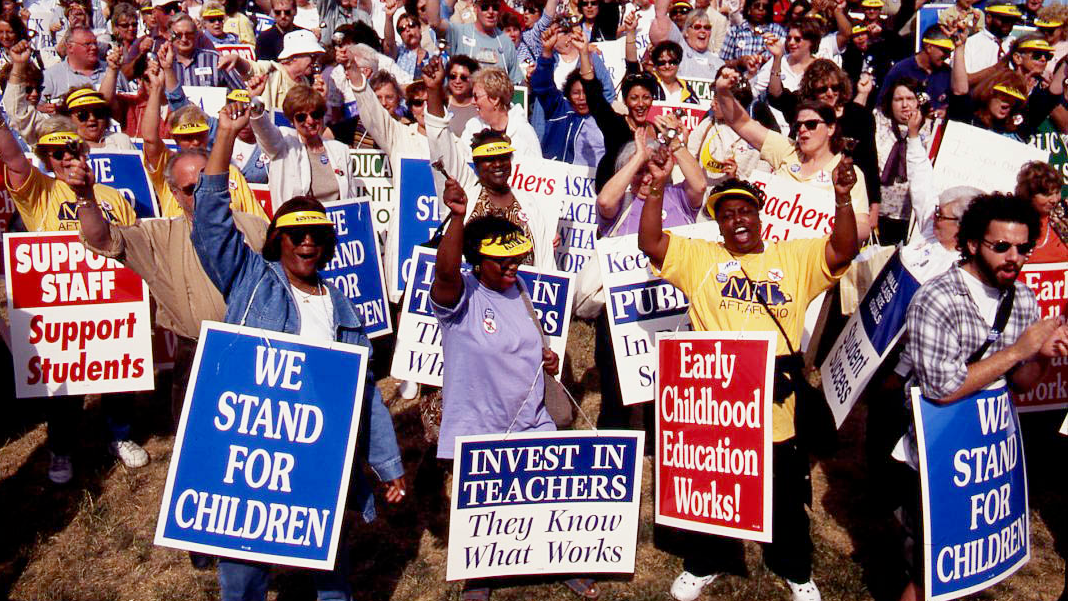

The ability to mobilize unionized educators was on display during a huge rally on Beacon Hill in 1999, when more than 15,000 educators marched, chanted and rang bells, demanding to be heard on matters that affected them and their students. These debates all came to a head in June of 1993.

On June 4, the House and Senate approved the massive Massachusetts Education Reform Act, which included an ambitious new funding system along with numerous policy changes.

On June 15, the Supreme Judicial Court ruled in favor of the MTA-backed plaintiffs in the case, McDuffy v. Robertson, determining that the state had failed to meet its constitutional duty to provide an adequate education to all students.

Three days later, Weld signed the education bill into law, to mixed reviews from the MTA on the policy provisions, but support for the increased funding. “This bill may be far from perfect,” wrote MTA President Robert Murphy, “but it gives a strong impetus to improve student performance, to stabilize and increase school funding and to enhance our own opportunities for professional excellence, while still protecting the basic due process rights of all educators.”

To this day, the 1993 law has shaped virtually all aspects of public education in Massachusetts. Key provisions are as follows:

Foundation budget. For the first time, the system set spending requirements for every district, specifying the minimum local contribution and how much the state must allocate to bring all districts to “foundation.” This led to a doubling of state funding for public schools, from $1.3 billion in 1993 to $2.6 billion in 2000, with most of the new money going to low-income districts. The additional resources were a tremendous help in the early years, though eventually the formula failed to keep pace with rising costs. In 2021, the foundation budget was substantially updated in the Student Opportunity Act.

Student standards. For the first time, the state had a mandate to establish learning standards by grade level, leading to the creation of the Massachusetts Curriculum Frameworks.

State assessment system. The law also required the creation of an “assessment system,” though that system largely rests on a series of standardized tests: the MCAS. At first these tests were just administered in grades four, eight and 10, but more levels were added later. Among other problematic applications, MCAS results are used to identify “underperforming” schools and districts and to determine which students are qualified for diplomas.

Just cause dismissal. The law abolished the teacher tenure system and replaced it with a “just cause” dismissal standard for teachers who had attained Professional Teacher Status.

Certification. The act established a process for certification — now called licensure — that has undergone several modifications since 1993 but still retains some of the original features. It required aspiring teachers to pass qualifying exams, now called the Massachusetts Tests for Educator Licensure.

Recertification. For the first time, recertification was required. Teachers were — and still are — required to be recertified every five years by participating in mandated professional development.

Charters and school choice. The state’s interdistrict choice program was expanded. The act also allowed the creation of privately run but publicly funded charter schools, though it initially capped the number at 25 statewide. The expansion of charter schools has been hotly contested ever since, most recently with the defeat of Question 2 in 2016.

School councils. Principals in each building were required to establish school councils that include parents, teachers, community members and, at the high school level, students.

The MTA spent much of the rest of the 1990s implementing, challenging or modifying various portions of the law. Some of the changes were welcome, while others, including the MCAS requirements, are still controversial.

"If you want to know how to make schools work better, ask a teacher.” Slogan used during 1999 rally on the Boston Common

The MTA’s ability to mobilize members was also on display throughout the decade. A large rally in 1992 was topped by an even bigger one in 1999 — likely the largest in the MTA’s history.

An estimated 15,000 to 20,000 educators shut down Beacon Hill on June 16, 1999, marching, chanting and ringing bells as they gathered at the State House.

Specific policy proposals catalyzed the rally, but the energy behind it was fueled by the demand that educators be heard on matters that affected them and their students. Their slogan was clear: “If you want to know how to make schools work better, ask a teacher.”

This is the fifth article in a five-part series that began in 2020, the 175th anniversary of the MTA’s founding. This is a lightly edited version of the article that appeared in the Spring 2021 edition of the MTA Today. This final installment is based on coverage in MTA Today.

Stories from the MTA’s History

In 1995, the MTA celebrated its 150th anniversary. MTA Communications published a booklet highlighting stories from the organization’s history since 1845 – since before the Civil War, women’s suffrage, the telephone, the automobile and mandatory attendance in public schools.

That history was updated in a five-part series celebrating MTA’s 175 years of activism, including recent battles fought against privatization of public schools and for education funding.

MTA founded at the birth of universal education in Massachusetts

Massachusetts is known as the education state for good reasons. The state’s commitment to education started early. We had the first public schools, and in the MTA, one of the first education associations.

What’s in a name?

The MTA has gone through several structural and name changes over the years, sometimes making it challenging to track the organization’s history — or even to determine which organization is the “real” MTA.

'The past is never dead. It's not even past.' – William Faulkner

Check out these stories from our past to present.

Has there been an educator strike near you?

Have the reasons for striking changed over the years? Check out the MTA's new interactive website on the history of strikes by MTA locals over the past 55 years.

“History is instructive. What it suggests to people is that even if they do little things, if they walk on the picket line, if they join a vigil, if they write a letter to their local newspaper … Anything they do, however small, becomes part of a much larger sort of flow of energy. And when enough people do enough things, however small they are, then change takes place."

American Historian Howard Zinn (1922-2010)